Motley Talk about Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

How a disappointment at the Tate took me down a research rabbit hole that led to Broadway.

Dear friends, since my last visit to Tate Britain1 they have rehung the pictures in chronological order. The gallery showing art from 1840 is now in a big, long room with the pictures displayed as they would have been during the Victorian era, when they were painted. This means the pictures are crowded together, three or four high, with minimal labels. The room is also a main thoroughfare, with tables of arts & crafts for anyone who feels artistic - mostly attracting chattering children.

I have sympathy with galleries as they try to display as much of their collection as they can. But the reason we no longer display pictures in the Victorian style is that it is IMPOSSIBLE TO SEE THEM PROPERLY. If you are a Bridgerton fan, in season one there was a comment about why a bad picture was “not skyed with the other daubs”. ‘Skyed’ means to hang a painting high up on the wall, above the line of vision, so it cannot be properly seen, as is done at the Tate. I was very upset.

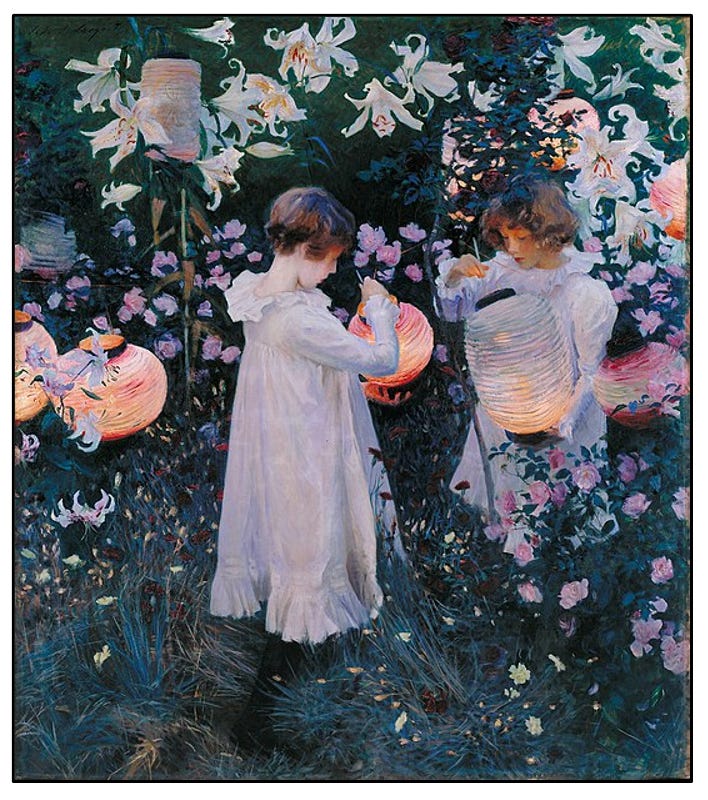

The principal reason for my visit was to take my daughter to see a favourite painting of mine, ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’ by John Singer Sargent. The picture should be seen in the original to appreciate its luminosity. It is not skyed but the muddle of so many pictures so close to it, and the noise in the room, made it impossible to sit still and contemplate the beauty of the painting - to let its light fill your soul.

So instead, I thought I would come home and learn more about this extraordinary painting.

The artist John Singer Sargent was born in Florence to American parents. Sargent’s father was an eye surgeon but he gave up his post, and the family (John and his younger sister Mary) then travelled around Europe. The family were not wealthy, so the children received only a basic education from their father. However, Sargent was encouraged to sketch, and they visited all the main art galleries in Europe. After art school Sargent continued to study at the studio of Carolus-Duran, who was a portrait painter.

In the past an artist sketched onto the canvas, then a thin underpainting was applied, before carefully mixing paints and painting so that no brush strokes could be seen. Carolus-Duran’s approach to painting was radical. He encouraged his students to draw and paint simultaneously, and also to build up colours directly on the canvas.

When Sargent finished his training, he travelled, but he was mostly based in Paris. He became a sought-after portrait painter. Until Madame X. In 1884 he displayed a painting of Madame Gautreau, an American beauty living in Paris. He renamed the picture Madame X (though everyone knew who she was). The painting caused a scandal, because it was seen as shockingly sensual.

French commissions dried up and Sargent contemplated giving up painting for music – he was a talented musician. Instead, he moved to London.

Sargent had many friends in England, including the novelist Henry James – they were both American expatriates.

Slowly Sargent revived his portrait painting commissions but he also began to paint landscapes, and in particular to paint outside.

Painting outside the studio before the 19th Century had been problematic. The easel and paraphernalia the artist needed were heavy and cumbersome. The artist also had to mix their own paints from raw pigments that they ground themselves. Mixed paints could be carried outside, in pig’s bladders or glass vials (very carefully). None of this made it easy to paint outdoors. However, John Constable made many oil sketches outside, before painting the picture back in the studio.

In the mid-19th Century technology came to the rescue. Synthetic paints were developed including Prussian blue to replace the extraordinarily expensive blue paint made from crushed lapis lazuli. Not that Constable had to use much blue for English skies or seas, but the impressionists in France made good use of the new blue paints. Also, the paints were ready mixed and available in tubes.

Another innovation was a box easel, that contained the paints, supported the canvas, and was easily transported. It was also around this time that photography techniques improved, making photographs accessible to all. Artists no longer had the responsibility to realistically record the world and the people around them.

Artists started to paint ‘en plein air’, an artistic expression meaning to paint entirely outside, in order to better capture the changing details of the weather & light.

When painting outside, the painting had to be completed quickly, to capture the changing light, which meant using Carolus-Duran’s technique of drawing and painting simultaneously. ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’ was painted entirely outside in order to capture the special light at dusk.

Sargent never married but he had a lot of friends. During the summers of 1885 and 1886, he enjoyed communal life as part of a small group known as the ‘Broadway Colony of Artists’. Broadway village2 is in Worcestershire, England. The group lived in several houses but gathered most days at the largest.

Sargent had previously seen Chinese lanterns hanging among trees and lilies, so he wanted to capture the scene in a painting. One member of the colony was the illustrator Frederick Barnard; his daughters Dorothy and Polly were the models for the picture, set in the garden of the main house the Broadway colony used.

Sargent was determined to get the exact moment at dusk when the light was just right. He would set everything up beforehand, then, as Edmund Grosse, who was also a member of the colony noted: “he took up his place at a distance from the canvas, and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time, rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only, with equal suddenness, to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied but two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then, while he left the young ladies to remove his machinery, Sargent would join us again, so long as the twilight permitted, in a last turn at lawn tennis.”

The painting took two summers to complete (1885 and 1886) and when the flowers died, they had to be replaced with artificial ones. The painting was named after a popular music hall song of the time, ‘Ye Shepherds Tell Me’ by Joseph Mazzinghi (1765 to 1844), which the folk at Broadway would have sung around the piano:

Ye Shepherds tell me Tell me have you seen, Have you seen My Flora pass this way? In shape and feature's beauty queen, In pastoral, in pastoral array A wreath around her head Around her head she wore Carnation, lily, lily, rose And in her hand a crook she bore And sweets her breath compose.

As always, any links are provided to give the reader more information. I do not make any money from these links. Where possible permissions have been sought for the use of images and text, unless they are in the Public Domain. If there is an issue with copyright please contact me.

Entry to Tate Britain, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG is free (apart from special exhibitions). To see their opening times and exhibitions click here. Displays change in the galleries and not all of their collection is on show.

There is no connection between Broadway the village in England, and Broadway the street in New York, USA. Though both were named because of the broad (wide) way (street).

Fascinated insight … my bug bear at Galleries is always the “hang” . They don’t do any “visitor “ research. You often can’t read the typed details of the painting or see the painting in detail because it’s “Skyed”. If I worked at a Gallery I’d walk round and check what was what from a visitor’s perspective. I’d care …