Motley Talk about George

Though a more accurate title would be 'What George saw in London, just before the Victorians changed everything'.

Dear friends, last week I wrote about Brompton Cemetery but I did not mention George Johann Scharf (1788 to 1860). He is not included in the list of famous people buried in the cemetery, and he is buried on the unfashionable west side.

George was a Bavarian draughtsman, who lived most of his life in London. He is not to be confused with his famous son, Sir George Scharf, the first director of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

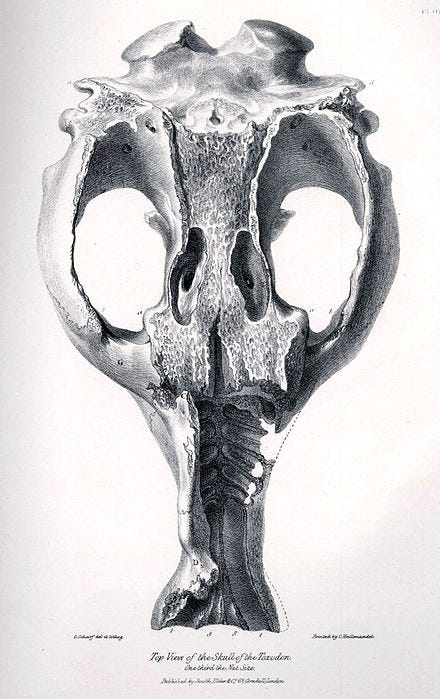

George Senior was known principally for his illustrations of scientific works. He produced minutely detailed lithographs of bones & fossils and other specimens for Charles Darwin, amongst others. George was a slow but meticulous worker, so his commissions were frequently late, he undercharged, and he hated to ask for money, so he was often in financial straits.

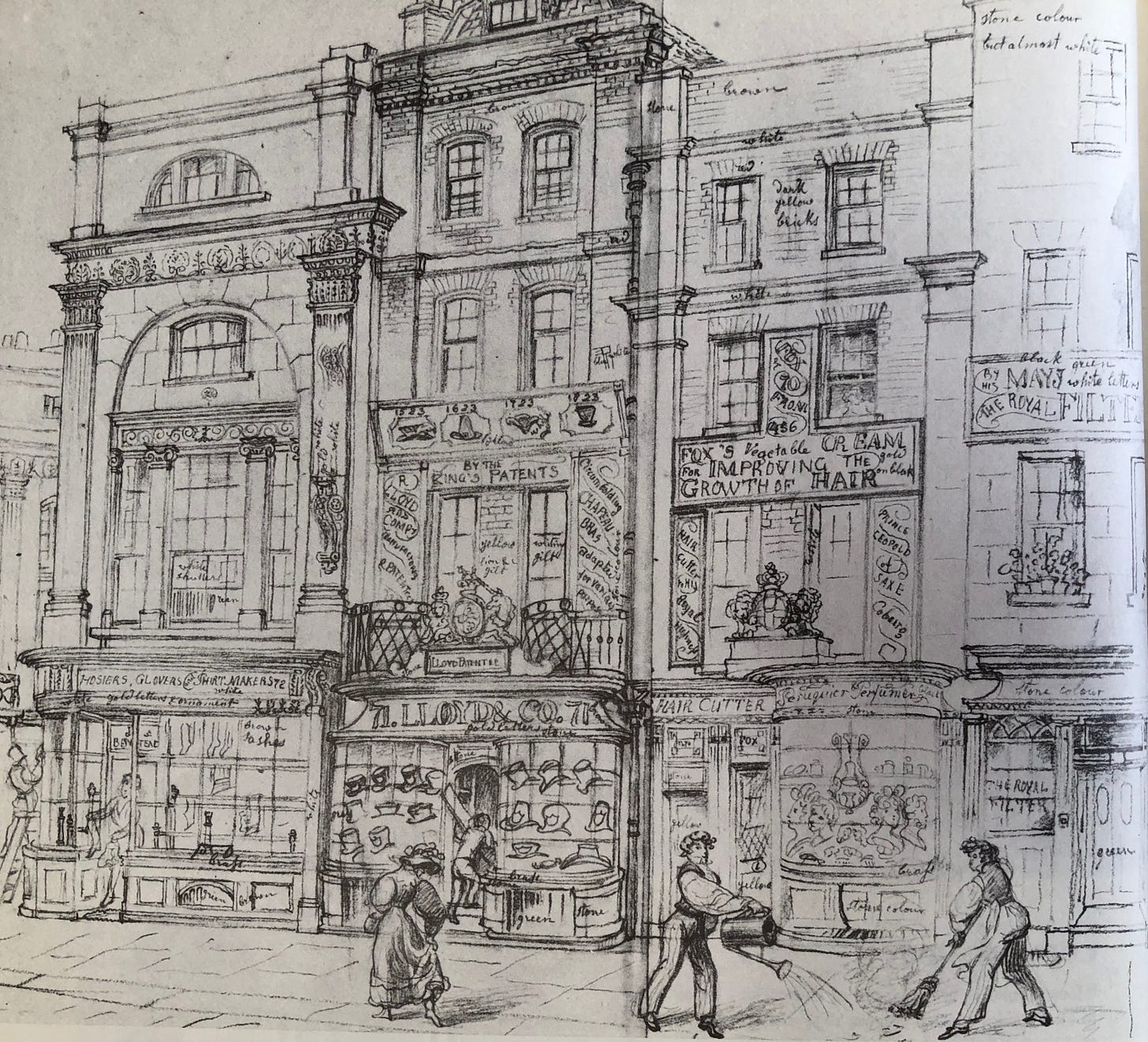

George found his work tedious and boring. What George really, really liked to do was sketch London and Londoners. At every opportunity he would pull out his paper & pencil. In his diary he remarked that he “sketched from the coach while horses were changing on the Cambridge Road”. He did try to sell his London paintings and drawings, but with very little success.

In later life George struggled to make a living. After his death aged 72, hundreds of his drawings were sold or given to the British Museum; there are also some drawings in private hands. His drawings remained bundled up for years, though they have now been sorted and can be seen at the British Museum.

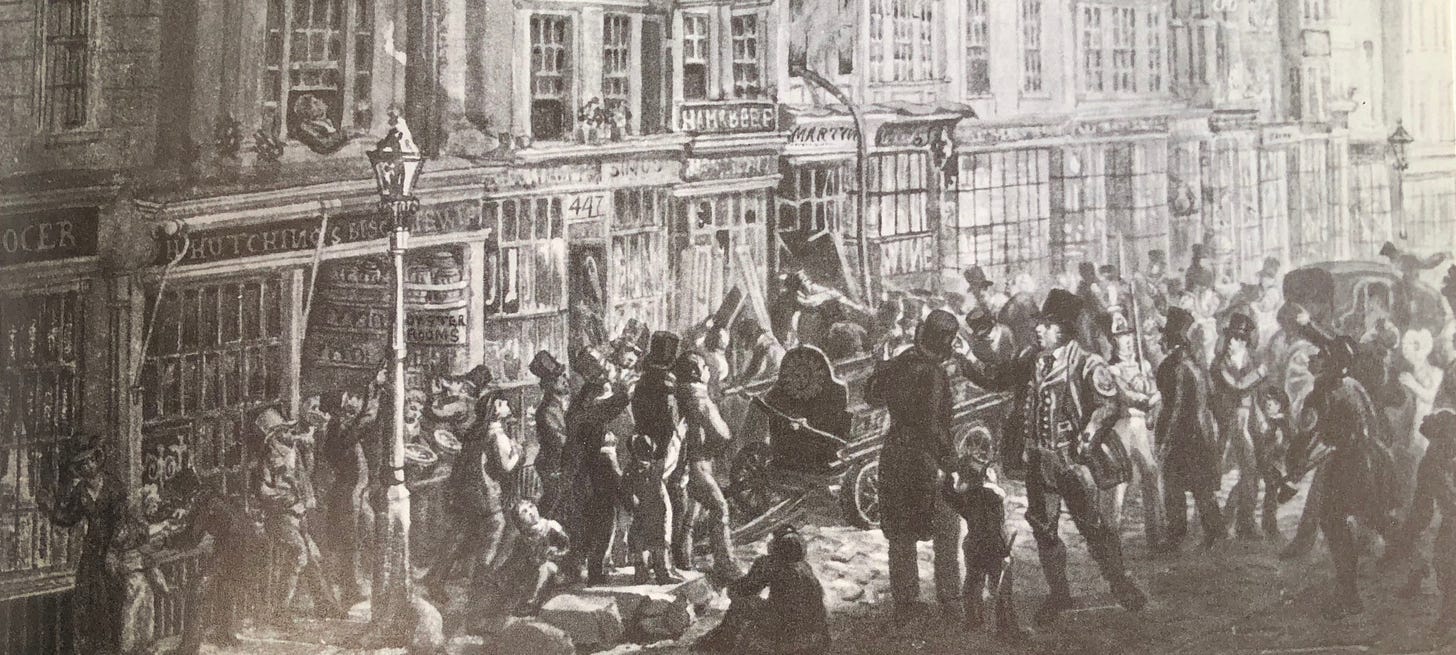

In 1987 Peter Jackson published an excellent book called George Scharf’s London1, gathering together many of George’s best drawings and adding interesting notes. The sketches from 1820 to 1850 show a changing London at the beginning of industrialisation. There are people going about their daily lives, often drawn selling goods or services on the streets. At the beginning of the 19th Century placard advertising started.

You can see an advertisement for Belzoni’s Egyptian exhibition. In October 1817 G. B. Belzoni discovered the painted tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings2. In 1821 Belzoni reconstructed two of the most important of the tomb's rooms for an exhibition, probably starting the Victorian craze for all things Egyptian.

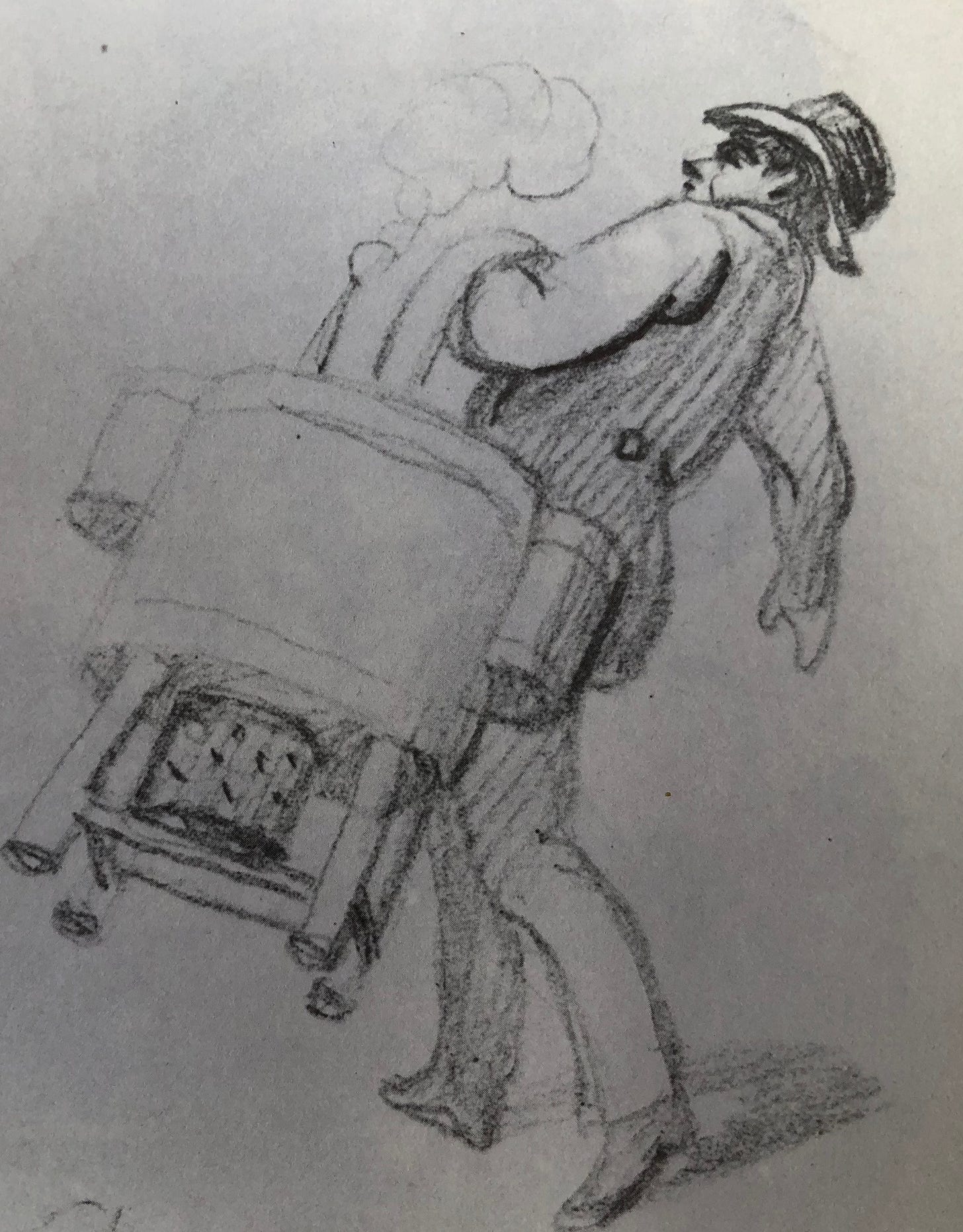

London has always had street traders, though due to strict trading laws they are rarely seen nowadays, certainly in central London. As long as there have been street traders in London there have been ‘street cries’, as traders proclaim the goods they are selling. Whenever we had baked potatoes for supper my grandmother would repeat the potato sellers cry of “heat your hand, heat your belly, for a penny”.

Other cries were sung in a round, like these strawberry sellers.

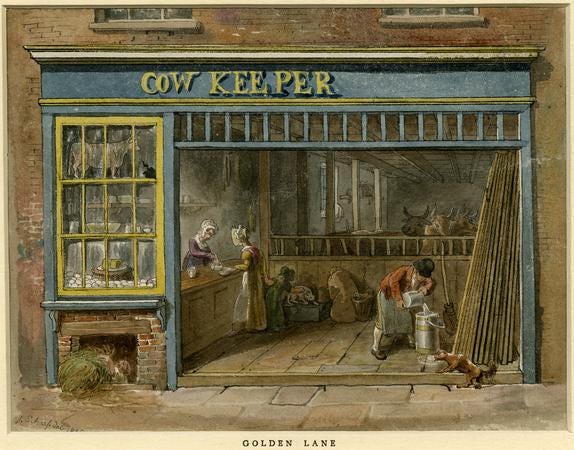

There were many dairy farms on the outskirts of London, but some dairies kept cows in town, as in this watercolour, so the milk was very fresh.

In the 19th Century fires were still a concern in London, as the houses were heated with open fires, with candles and oil lamps used for light. Before the 1666 Great Fire of London there were no official fire brigades, just whoever turned up with a bucket of water, to fight the fire. But after the disaster of 1666, insurance companies ran their own fire brigades (called a fire offices), and people paid a fee to the company.

Most fires were attended by a fire engine, regardless of the insurance paid, because of the risk to surrounding buildings. But a house that was insured had a metal fire plaque from the relevant insurance company, placed high up on the outside of the house (so it was difficult to steal). You can still occasionally see plaques on old houses in London.

Presumably if the company did not find the plaque after the fire, you had to pay for the fire fighters who had attended the fire. On 22 June 1861 a fire started at Cotton's Wharf, where many warehouses were situated, filled with a huge array of flammable goods. It was the biggest fire since 1666. The blaze was so hot that firefighters struggled to get close enough to pour water from the River Thames on to the flames. But 30,000 Londoners still flocked to the area to see the spectacle.

It took two weeks to extinguish the fire and the damages cost an estimated £2 million – mainly for the contents of the warehouses (around £166 million today). £1,100 (£90,000 today) was paid to the pumpers, the men pumping water from the manual fire engines. In 1862, the insurance companies wrote to the Government stating they could no longer be responsible for the fire safety of London, and it should become a Government responsibility. On 1 January 1866 the Metropolitan Fire Brigade started.

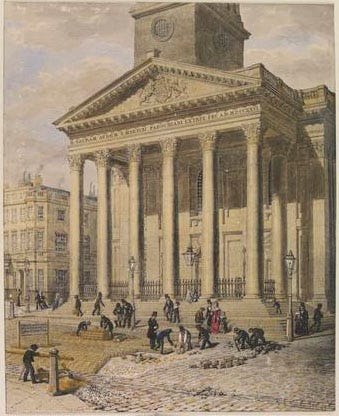

George was interested in all the changes occurring in London, and he drew the new wooden roads being placed to dampen the very loud noise of the wheels of carriages, and the clip clop of horses’ hooves on stone cobbles. At the time the upkeep of the roads depended on different parish councils, so there was no co-ordinated approach across London (one could say that is still the situation!).

There were some problems with wooden roads. While wooden blocks were quieter than cobbles, they had a tendency to absorb what fell upon them, mostly horse urine, and on hot days the stench was said to be terrible. Also, the wood was slippery when it rained and water could build up underneath the blocks, causing them to expand and becoming a trip hazard, and wood decays. Nevertheless, paving the streets with wood became a popular option across the world.

After the damage to London roads during the second world war, the wooden road surfaces were replaced with asphalt. Londoners used the wooden blocks as fuel. The last surviving section of wood paving in London is on Chequer Street, in East London, though there are some manhole covers still filled with wooden blocks.

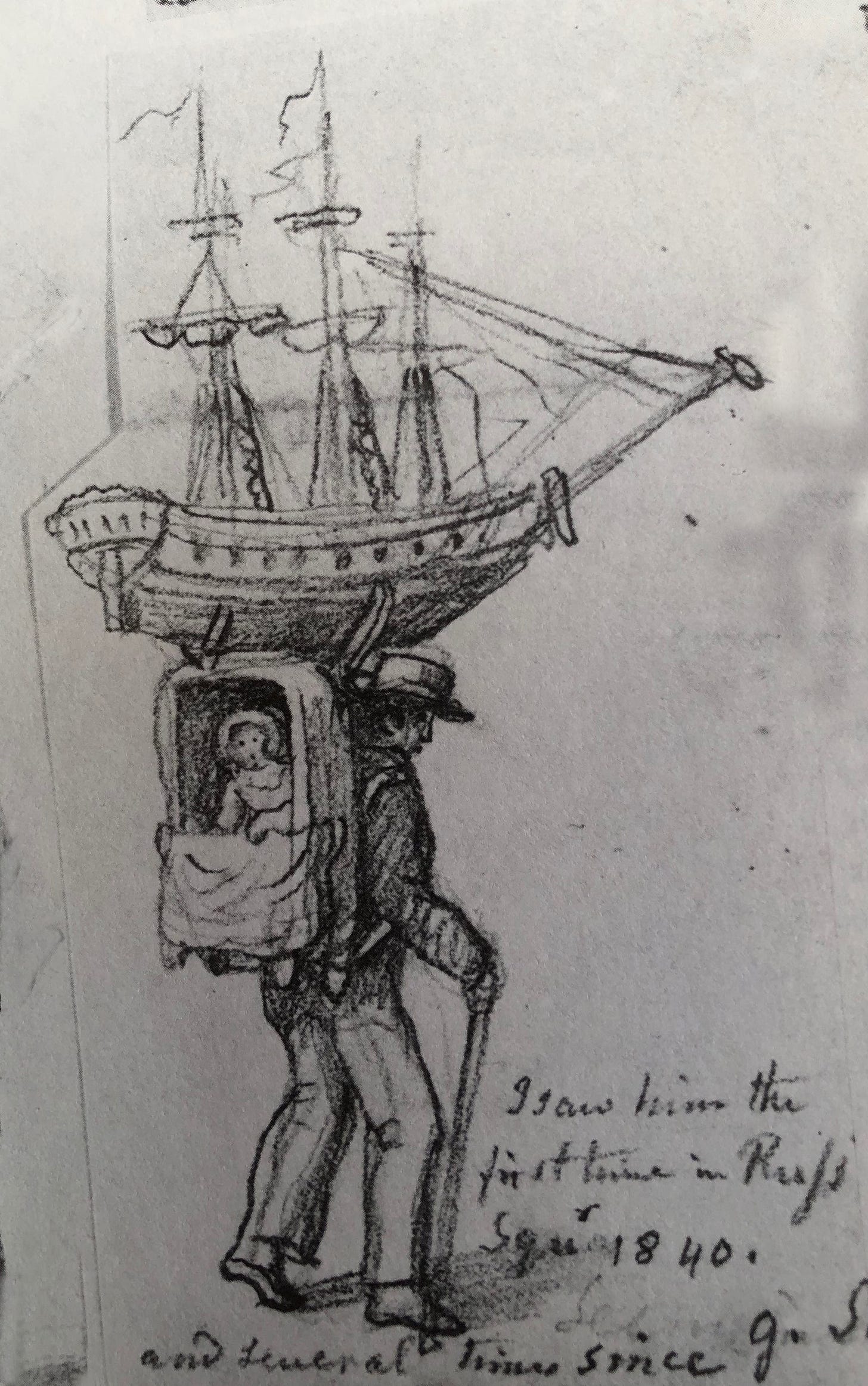

Lastly, I could not resist including the sailor with the model ship on his head and a child on his back.

Apparently he was seen by George on several occasions over 10 years, but no mention is made by him or Peter Jackson about what the sailor may be advertising or promoting. Or was he asking for work on a ship or offering to build another model ship for a price? How was the ship carried, if the child carrier was not used…? Any comments welcomed.

And so, we bid farewell to George’s lovely illustrations of early 19th Century London. Thank you George Johann Scharf, I think you deserve to be famous.

As always, any links are provided to give the reader more information. I do not make any money from these links. Where possible permissions have been sought for the use of images and text, unless they are in the Public Domain. If there is an issue with copyright please contact me.

It is out of print but you can buy it second-hand.

The Sarcophagus of Seti I is now in the wonderful, and frequently mentioned (you really should visit) Sir John Soanes Museum, in London.

So interesting. I really want to know about the ship now too.